By Snorri Páll Jónsson Úlfhildarson

On Friday September 2, two men appeared in court in downtown Reykjavík. It wasn’t their first time—and it probably won’t be their last. If found guilty, the defendants, Haukur Hilmarsson and Jason Thomas Slade, face up to six years in prison, due to a peculiar action on their behalves that marks a turning point in Icelandic asylum-seeker affairs.

On the morning of July 3, 2008, Haukur and Jason darted onto the runway of Leifur Eiríksson International Airport in Keflavík, hoping to prevent a flight from departing, and deporting. Inside the plane, which was headed to Italy, sat one Paul Ramses, a Kenyan refugee. The two activists ran alongside the plane, and placed themselves in front of it—halting its takeoff.

It would be wrong to assume that anything has changed since 2008. Iceland may have seen an infamous economic collapse followed by a popular uprising and a new government, but for the two activists it must feel like time is standing still. Since their arrest at the airport, they have been stuck in a seemingly endless legal limbo, first charged for housebreaking and reckless endangerment and later thrown between all levels of the juridical system. Last Friday, the case’s principal proceedings took place for the second time in Reykjavík’s District Court, after the courts original sentences were ruled null and void by Iceland’s Supreme Court.

THE ICELANDIC STATE VS. PAUL RAMSES

Paul Ramses originally arrived in Iceland in January of 2008. The year prior, he had unsuccessfully participated in Kenya’s general elections on behalf of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). Many Kenyan and trans-African associations claimed the electoral victory of ODM’s main opponents, the Party of National Unity, to have been rigged behind the scenes. The ensuing wave of fatal protests and riots had brought down 800 people by late January, and as ODM members faced mass persecution, Paul and his wife Rosemary fled Kenya and escaped to Iceland via Italy.

Paul Ramses and his wife Rosemary fled Kenya in 2008, afraid of their lives due to mass persecution against members of a political party that Paul was involved with. Shortly after their arrival, Rosemary gave birth to a son they named Fidel, thereby establishing her right to stay along with the newborn. Paul, on the other hand, needed to apply for asylum. The Directorate of Immigration (UTL for short) refused to take up his case and ruled for him to be deported to Italy. Although their ruling was made in April, Paul however wasn’t notified until three months later, the night before he was to be deported, when he was arrested by Icelandic police and separated from his family—an act that violated both his rights to appeal UTL’s decision and his son’s internationally protected right to stay with his parents.

WHAT IS THE DUBLIN REGULATION?

UTL’s decision to refuse Paul asylum was argued for by citing the Dublin Regulation, an agreement on asylum affairs implemented by the member-states of the Schengen Area. The Dublin Regulation permits authorities to deport asylum seekers to the first Schengen state they entered, but it does not oblige the state to deport the asylum seeker in any way—and, as a matter of fact, specially bids authorities to apply it in harmony with human rights conventions. However, UTL’s official policy has been to start every asylum application process by checking if it can be outsourced to another Schengen state.

That sort of policy is certainly not to lighten the burden of states—such as Italy, Spain and Greece—that are located at Schengen’s south and east borders (in 2008, 31.200 asylum application were filed in Italy, compared to 72 in Iceland). The South-European asylum seekers’ dilemma has been the subject of a multitude of damning studies and these three countries’ refugee policies have been heavily criticised by the likes of UN Refugee Agency, Amnesty International and European Parliament.

According to Jórunn Edda Helgadóttir, MA student of international and comparative law, The Dublin Regulation brings forward grossly defective rules that have allowed the Icelandic state to deport asylum seekers en masse by stating that “because everybody does it, we can too.” This was indeed how Björn Bjarnason, then Minister of Justice, replied upon being heavily criticised for the deportation of Paul Ramses: “Of course there is nothing unlawful or wrong with employing this treaty, any more than other international treaties.”

Such a statement is wrong, according to Jórunn as Iceland has validated the European Convention of Human Rights, in which it says that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,” and that “everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life”—two of many law paragraphs that were not considered in the case of Paul Ramses. “The focal issue at stake is will”, she says, as the “problem would never grow to be so huge if most governments weren’t so willing to pass their duties and commitments on to other states.”

“WE INTENDED TO SAVE HIS LIFE…”

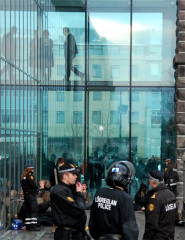

Back at the airport, Haukur and Jason were arrested and air traffic continued after a short delay. Interviewed by online news outlet Vísir shortly after his release, Haukur cut the crap when asked about his and Jason’s motives. “We intended to save Paul Ramses life,” he said, expressing worries that they had failed. Surprisingly, the next day, hundreds of people assembled by the Ministry of Justice and demanded Paul’s return to his family in Iceland.

The pressure increased with daily demonstrations, petitions and parliamentary debates, as well national and international media attention—all of it to be diagnosed as “sentimentality” by Minister of Justice Björn Bjarnason. But eventually Björn himself succumbed to “sentimentality” and overturned UTL’s decision. Parallel to the aforementioned pressure, Paul’s lawyer Katrín Theodórsdóttir issued a complaint to the Ministry, demanding material handling of Paul’s asylum application from a humanitarian standpoint. Following the Ministry’s ruling, UTL finally granted Paul asylum.

“…AND WE DID”

Today Haukur believes that although the impact of a single act of direct action is hard to measure, he and Jason actually saved Paul’s life. And their action, he says, paved the way for what followed, as standing in front of a ministry or signing a petition requires much less effort than running in front of an aeroplane. In the aftermath, they claim, people were less afraid to protest. Using the same logic, he insists that the good number of direct action such the ones of environmental movement Saving Iceland, which both him and Jason have also been involved in, paved the way for the so-called ‘pots and pans revolt’ of 2008-9.

At the same time he believes that The State’s response to such actions, for instance by instigating serious court cases, is likely to keep newcomers from getting involved. “It is sad that people have to make such enormous sacrifices for such tiny changes,” says Haukur and mentions Þorgeir Þorgeirsson, an author who in 1994, after a ten years long fight, won a historical victory at the European Council of Human Rights. Þorgeir had been sentenced in Iceland for his articles decrying and depicting police brutality in Reykjavík. Even if proven right, public innuendos regarding state or city officials was illegal at the time—something that wasn’t altered until the European Council ruled in Þorgeir’s favour.

THE ICELANDIC STATE VS. HAUKUR AND JASON

Haukur and Jason were originally charged with housebreaking and reckless endangerment. But once in court, the prosecutor brought forward two additional penalty clauses not included in the original charges, which he encouraged the judge to take into consideration. Such a move is not only illegal, but also in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights, which states that everyone charged with a criminal offence should be given adequate time and facilities in preparing their defence.

Despite protest from their defence lawyer, Ragnar Aðalsteinsson, who had to defend his clients unprepared for these new clauses, the District Court found the two guilty. Haukur was sentenced to two months in prison while Jason was given a 45 days probationary prison term, a ruling that the two appealed to Iceland’s Supreme Court. And while the Supreme Court judges did agree with Ragnar regarding the illegitimacy of the District Court’s ruling, they didn’t rule for the case’s discontinuation. Instead of acquitting the two, the Supreme Court’s judges made the unusual decision to send the case back to District Court, to start from scratch again.

According to Hrefna Dögg Gunnarsdóttir, law student and employee at law firm Réttur, the Supreme Court’s ruling surely manifests that Iceland’s uppermost court of law recognised the prosecution’s illegal move. Yet the decision to grant the prosecution another chance crystallises the fundamentally different position of the prosecutor and the defence. “This could be compared to a basketball game, in which one of the two competing teams always gets the ball after a failed throw,” says Hrefna.

Does this mean that they should have been acquitted? Not necessarily, if looked at by the book of law. But when viewed in context with the fact that by granting Paul asylum, UTL—and thus the Icelandic state—recognised the threat he faced if deported to Kenya, one has to wonder why the courts still questions Haukur and Jason’s actions.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE?

“The purpose of the charge is obviously to suppress resistance,” says Haukur. “I stopped hoping for an acquittal. Instead I use this case to learn how to analyse State Power, and to educate myself about this system and how it operates.”

During the procedure last Friday, one could witness the findings of Haukur’s studies as he delivered his 8.000 word’s long disputation—his own theory on the constant clashes between The Individual and The State’s innumerable tentacles. One of the more interesting points he made regards the humiliation entailed in having to discuss important issues on The State’s terms. While having ideologically argued for his actions, he claims he has constantly been met with idiotic and irrelevant questions; while wanting to discuss an important topic as refugee policies surely is, he has been met with a debate about fences and police regulations.

The prosecutor indeed questioned Haukur and Jason extensively about their entrance onto the airport driveway, about alleged signage that was supposed to forbid their entrance and why they didn’t obey orders from airport staff. The prosecutor, however, showed little or no interest in discussing the motives behind their actions, which usually is considered an important factor in criminal cases. Instead of entering an ideological dialogue with the defendants—a discourse that could eventually force him to face the overall legitimacy of their action—his obvious aim was to get them jailed for a mindless and dangerous criminal act.

Haukur has given up hope for an acquittal, but will admit that a victory in court would serve as an exemplary beacon for future cases against political dissidents, not to mention the legal and bureaucratic amendments it could lead to. But these are not these fundamental changes he hopes for. “The impact of these kind of cases on the behaviour of State Power can certainly lead to minor reforms, but the knowledge we can gleam from it can give rise to revolutionaries.”

______________________________________________________________

A shorter version of this article was published in the Reykjavík Grapevine magazine (p. 26).

Excellent post! We will be linking to this particularly great

post on our site. Keep up the good writing.