Michael Chapman

When it comes to loving where you’re from, Iceland has a fantastic international reputation for its widespread use of renewable energy, its untouched landscapes and its sustainable environmental policies. But just how true is Iceland’s positive attitude to the environment?

How are phenomena such as climate change, heavy industry and tourism affecting the landscape, the wildlands, the glaciers and the seasons of the country? Most importantly, how are the Icelandic people responding to these threats, if at all?

There can be no denying, nor any hope of denying, Iceland’s staggering aesthetic beauty. Icelanders themselves are quick to point out their spiritual connection to the land, understandably proud and protective of their country’s many highlights; its geological marvels, breathtaking panoramas and stunning natural scenery.

With rolling black sand beaches, mist-wreathed mountainscapes, cerulean glacier tongues and bubbling hot springs, Mother Nature has candidly outshone herself decorating this small, Atlantic island.

Needless to say, this array of diverse splendour has been the most significant cause of Iceland’s tourism boom over the last decade. Over this ten year period, an inundation of foreign guests has shown to encapsulate for the Icelanders: economic prosperity, threats to the environment and the necessity for a dramatic change in thinking – particularly in how Icelanders see themselves, their foreign guests and the world around them.

The unanticipated sweeping manner in which the tourism industry has cajoled influence and control in Iceland has aroused a number of polarising questions in the population’s collective consciousness, most importantly, how can Icelanders protect and maintain their symbiotic balance with the natural world?

An Increasingly Complicated Situation

To answer this question, both Icelanders and their foreign guests must first address their own troubled history with the environment. They must question their own personal values and do away with yesterday’s appraisal of the situation. As has been said repeatedly of an exponentially unstable environment, the time for indecision and quiet contemplation has already passed.

This might, at first glance, be considered rich coming from an escaped Englishman. After all, our own national track record in dealing with environmental issues leaves much to be desired. Nevertheless, it is exactly because I am an outsider in this arresting land that the issue of appreciating and educating oneself to the subtle harmonies of nature resonates so deeply with me.

I, alongside my fellow Guide to Iceland colleagues, have no desire to see this wild, untameable, ethereal living-world be lost to the gallows of ignorance, greed and misjudged development. Neither too should the people more intricately connected to this land than me—the fishermen, the farmers, the men and women whose roots are bound forever to this northern landscape.

And yet, the nature of human beings is eternally skewered by defects in our neurological makeup. Our eyes are constantly drawn aside from the beauty in front of us and instead averted to outside indulgences; our greed, our compulsive desire for order, our subjection to and resistance of our place in the universe.

Consider it; before the tourism boom, it was the driving will of the then Icelandic government to dramatically maximise the country’s economic output. This is unsurprising, of course, given that all governments look to secure wealth ample enough to provide for their respective society. It was, however, the means in which the overseers chased, for lack of a better word, that “Yankee dollar”—the introduction of heavy industry, hydroelectric dams and aluminium smelters.

Despite heated opposition and a growing anti-industry consensus, many Icelanders felt, and still do, that it is Iceland’s nature who, again, bears the brunt of any new economic venture. Today, the heavy industry issue has become intrinsically interlinked with the threats (and perceived benefits) of an exponentially lucrative tourism trade.

Of course, the situation becomes ever more confused, ever more disguised, ever more pushed under the rug. This trend is in no way unique to Iceland, but it does seem strikingly paradoxical considering the country is a cornucopia of natural splendour. Many Icelanders themselves point this out; others are living in a kind of collective delusion, a need to go somewhere, to progress at all costs, to turn Iceland into what it could be rather than what it is.

As an example of this mindset, greenwashing has become something of a staple practice amongst thousands of businesses, not just in Iceland but worldwide. Take the low-cost Icelandic airline Wow Air; by blending obtuse environmental policies, collecting daily donations and pushing a well-financed marketing campaign, the company has declared itself on the right side of sustainability.

Considering the company derives the bulk of its profits from tourists flying back and forth, thus strengthening enormously the correlation between air travel and carbon emissions, the truth is decidedly more slippery. There are a number of sites out there, such as Carbon Footprint Calculator, which demonstrate evidentially the negative impact that airlines have on the atmosphere.

WOW Air Iceland Airbus. Wikimedia. Creative Commons. Credit: BriYYZ

This same accusation of conscious hypocrisy could be pointed toward the Icelandic government, a government who in the past have short-sightedly claimed “Iceland is the greenest country in the world,” as though no-one might think to question such a boast. But is this deliberate and direct misinformation or simply the said collective-delusion; a positive assumption derived from misunderstanding, national pride and unclear thinking?

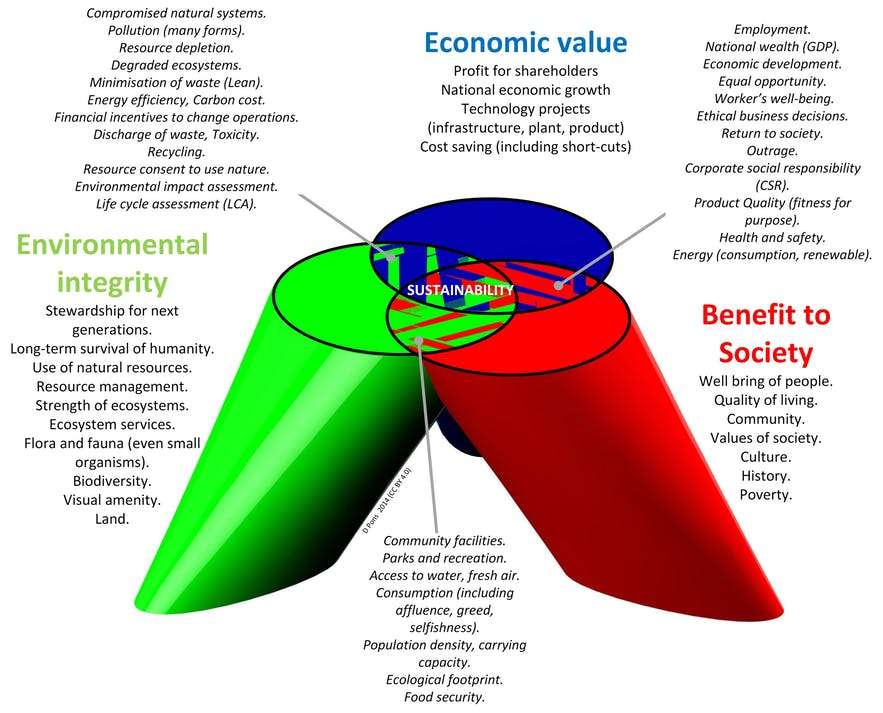

To give you some idea as to the factors that need balancing while attempting to achieve economic and environmental sustainability, I have included below a model entitled, ‘The Three Pillars of Sustainability.’ At the top of the pillars’, the conflict of values we are discussing here become abruptly apparent.

Three Pillars of Sustainability. Wikimedia. Creative Commons. Credit: Dirk Pons.

Many, both in Iceland and abroad, have pointed out that Iceland’s statistics for environmental sustainability and management are highly skewered by the country’s small population. On average, carbon emissions per person far outweigh that of European counterparts and, like many other Western democracies, the population’s apparent devotion to wasteful consumer culture is a prevalent force. Because of this, Iceland’s ecological footprint is one of the highest in the world, a whopping 12.6 acres of necessary resources per person.

Chairwoman of the opposition Left-Green coalition, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, conceded that “If everybody lived like Icelanders, we would need six planets, maybe more.” Thankfully, her opinion has, over time, began to make a hearty impression on Icelanders across the country.

But what are the historical roots that underlie the Icelander’s subconscious hostility to the environment and how do they reflect the attitudes of today’s population?

An Ancestral Attitude

The natural disconnect between individuals and their environment—the illusory sensation that they are, in some sense, separate from it—is long rooted in history, in outdated ideology and in cultural misunderstanding.

Long before globalisation or the advent of scientific reasoning, an individual’s relationship with the physical world was necessitated largely by biological need, namely food and shelter. Naturally, this often led to irreversible damage to the environment such as deforestation and the extinction of native species.

To push this point, when Iceland’s earliest settlers first saw their new homeland, it resembled nothing of what it does today. The uninhabited landscape was around 60% covered with birch forest and woods, perfect for a new and resourceful agrarian society. The earliest sagas state “At that time, Iceland was covered with woods, between the mountains and the shore […]” insinuating that, at the time of writing, Iceland’s forest cover was already diminishing.

Irrespective of that, within months of landing, settlers were chopping down the forests to create grazing lands for their sheep and cattle, utilising the wood to build farmsteads, trading posts, equipment and boats. Given the sheep’s appetite for green vegetation, the process of soil erosion quickly began after it was left exposed to the elements.

Granted, there were a number of other environmental factors that contributed to the overall deforestation of Iceland, including a cooling climate and volcanic disturbances, but it was the widespread grazing of sheep and the subsequent soil erosion that acted as the primary catalyst.

Around that time, it is suspected that Iceland lost 90% of its woodlands and 40% of its soil. Because of the environmental destruction that ensued during the settlement of Iceland, and the devastating impact it had on the island’s original ecology, some contemporary Icelanders, such as film director Hrafn Gunnlaugsson, have claimed Iceland to be “the most polluted country on the planet.”

This is, of course, something of an overstatement given the transient nature of one’s environment (especially over many centuries), but it does take into account how the Icelandic people and their land have been at odds since the earliest days of the country’s inhabitance.

From Norse Paganism to Christianity

It could be suggested that this feeling of disconnection and superiority over nature arose as a particularly self-assured philosophy in 1000 AD when Icelanders converted on mass from Norse Paganism to Christianity. In doing so, an enormous re-evaluation of the individual’s place in the world and their relationship to it was a necessary cultural undertaking.

Built in the image of God, and thus servant to him, it is beyond plausible that the people’s attention was drawn away from the life in which they existed, and instead was focused toward a life after death; an afterlife defined by the actions of the present moment.

In thinking this way, Icelanders could quickly affirm the impermanence of nature and thus pin a trifling importance to it. Why, after all, should the conscious preservation of nature matter if this world was made as the playground, the arena, the stage for solely human endeavour? What delights await in the world after this?

Though Norse Paganism can not be considered in any way similar to contemporary environmental movements, there was still a foundational belief that the sacredness of nature was at the core of an individual’s experience.

This was interweaved, of course, with a polytheistic belief in multiple Gods and a pantheistic worldview that reality mirrors the divine. Both of these ideas, arguably, were lost to many people upon the countries conversion to monotheism.

20th Century Lines of Thinking

In the twentieth century, an amalgamation of ecological and pagan perspectives merged to what would later become known as Ásatrúarfélagið. Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson was one of the instrumental founders, having helped conceive of the practice in a Reykjavík cafe in 1972.

Turning its back on dogmatic thinking, this neo-pagan philosophy sought to return an individual’s balance with nature, albeit still through ritualistic practises and ceremonies. The religion would act as a sanctuary from the pressures of a developing world and focus itself on the belief in the land’s hidden forces.

Ásatrúarfélagið, in many respects, could be seen as a twentieth-century reaction to the individual’s growing disconnect with nature, adopting pagan practises and principles reminiscent of those practised before the Christianisation of Iceland.

The philosophy was also clearly indicative of a growing feeling amongst modern Icelanders; this growth did not need to be overtly spiritual as it still locked on to the concept that people’s preconceived notions of nature were wrong. This gradual change in thought process dates back to the beginning of the century and is made all the more clear when considering the blunt differences between a rural and urban perspective on the environment.

Halldor Laxness’ short novel ‘The Atom Station’, published in 1948, revolves around the American purchase of an Icelandic bay so that they might strategically avert a nuclear war with the former Soviet Union.

Laxness uses his country-girl protagonist, Ugla, to describe the mid-twentieth century divide between a rural and urban perspective of nature;

The environmental movement has, arguably, been a part of Icelandic society since as early as 1907, when efforts were made to fight the rise in soil erosion. In the same year, the iconic waterfall Gullfoss was subject to an ownership bid. A British businessman, known only as Howell, proposed to Gullfoss’ then owner, Tómas Tómasson, that he would buy the waterfall and utilise its raw power by constructing a hydro-electric dam.

For many years after, Tómas’ daughter, Sigriður Tómasdóttir, was entangled in a legal battle in order to save the waterfall from development. Her passion and drive were so forceful that, on many occasions, she would walk from Gullfoss to Reykjavík just to make sure her concerns for the country’s nature were heard. On such occasions, it was not unheard of that Sigriður might threaten to throw herself from the falls should construction of the dam begin.

Fortunately, the former owners could not maintain the costs of owning Gullfoss and, in 1940, the land was sold to the Icelandic government. Because of Sigriður’s efforts, she is often cited as Iceland’s first environmentalist.

Much like elsewhere, however, the movement became somewhat unified during the 1970s, though it still lacked the political power and support of its overseas counterparts. Instead, ideologies prominent in the environmental movement were adopted alongside other socio-economic thoughts, finally culminating in the Left-Green party of Iceland. This political party has long been the second largest political party in Iceland.

One of the key ideologies that drive the environmental movement is an inherent desire to save and protect nature for its own sake. This stands in antagonistic parallel to the consumer culture that prevailed throughout the twentieth century; whereas environmentalists pushed the need to recycle and reuse, burgeoning capitalists strengthened the idea of demand and supply.

Contemporary Environmental Issues

Today, it is clear that the culture of Capitalism, though not inherently evil of itself, has dominated the lifestyles of many people in Iceland and, thus, has led to wild abuses of power.

The Perils of Heavy Industry

Saving Iceland protest. Credit: Saving Iceland

Per capita, Iceland produces more electricity than any other country on the planet. This is due almost entirely to the wealth of renewable energy on offer, an excess that is naturally seductive to overseas corporations looking to maximise their profits. This means that in one sense Iceland’s electricity is the cleanest in the world. On the other hand, it means that opportunities to abuse said abundance are far more common and tempting.

Unsurprisingly, the Icelandic government does not find this outside interest off-putting, but rather flirty and attractive. A ‘friends with benefits’ type situation significantly increases a country’s national GDP, provides thousands of jobs and attracts further foreign investment. For those holding the briefcase, capitalising on the resources at hand is something of an economic turkey shoot, an easily accessible method of transforming something priceless to gold.

Saving Iceland protest. Credit: Saving Iceland

Companies from Australia, Ireland and the US all export bauxite to Iceland for aluminium smelting, using the cheap energy for efficiency and capital gain. Because of this, Iceland made provisions to increase its carbon emissions under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol at a time that all other signatories pledged to cut their own.

Perhaps, given what we know, this should not have come as such as surprise. Iceland’s economy has always been export-driven; first, it was fish, then the exporting of manufactured goods and now finally, the export of nature itself, be it room for heavy industry or, paradoxically, as an allure to foreign visitors.

Icelandic author and filmmaker, Andri Snaer Magnason, director of the environmental documentary ‘Dreamland’, has claimed particularly of Iceland’s reliance on aluminium that the country is engaged in an unhealthy ‘heroin economy’; it is a cultural addiction to an unsustainable and ultimately self-destructive practice.

The Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant

Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant and the subsequent Kárahnjúkastífla Dam is the centrepiece of five major dams in Iceland, having been opened amongst much controversy in 2009. It is the largest of its kind in Europe, having been constructed to provide energy to Iceland’s aluminium smelting industry.

Since its inception, environmental groups have strictly opposed its operation on the grounds that it causes irreversible environmental damage to the surrounding area. This would include devastating the habitat of pink-footed Geese and wild reindeer. The hydropower plant has also been criticised for exploiting foreign workers.

Saving Iceland protest. Credit: Saving Iceland

Saving Iceland is one such environmental group who took action, forming an activist camp at Kárahnjúkar in 2005. Immediately, construction on the dam had to be halted, with police called to deal with the groups’ protest.

Building on this, Saving Iceland has continued to stage protests against various other construction projects throughout the year and earned themselves quite the reputation in doing so.

Saving Iceland protest. Credit: Saving Iceland

The Icelandic media was quick to jump on the group, making the claim that they were ‘G8 Anarchists’ trying to disrupt the very fabric of the country. To the activists themselves, they were simply countrymen trying to save their land from the greed of large multi-nationals.

Aluminum Smelters

Iceland has three aluminium smelters which, since their inception, have done nothing but cause heated debate amongst Icelanders. The aluminium smelters are found in Reyðarfjörður in East Iceland, Grundartangi in West Iceland and Hafnarfjörður in the south-west. In 2010, 73% of the overall energy usage in Iceland was directed toward these aluminium smelters.

Aluminium Smelting Factory.

From the beginning, the government attempted to sway the Icelandic people in favour of smelting aluminium, claiming the plants used clean geothermal energy and, therefore, the country was making a positive contribution to alleviating the climate crisis.

According to the government, Iceland was only responsible for 2% of the aluminium smelting production worldwide, making it an important ‘source of employment for the modern age.’

This source of employment, however, meant that Iceland needed the heavy infrastructure to deal with this new industry. In full spirits, and to the chagrin of many of the Icelandic people, the government set about constructing large dams, geothermal plants and kilometre-long factories.

In truth, the land around the aluminium smelters has been measured for pollution approximately every five years or so, and with it has come strong evidence that the smelters do in fact cause a high level of soil and air contamination.

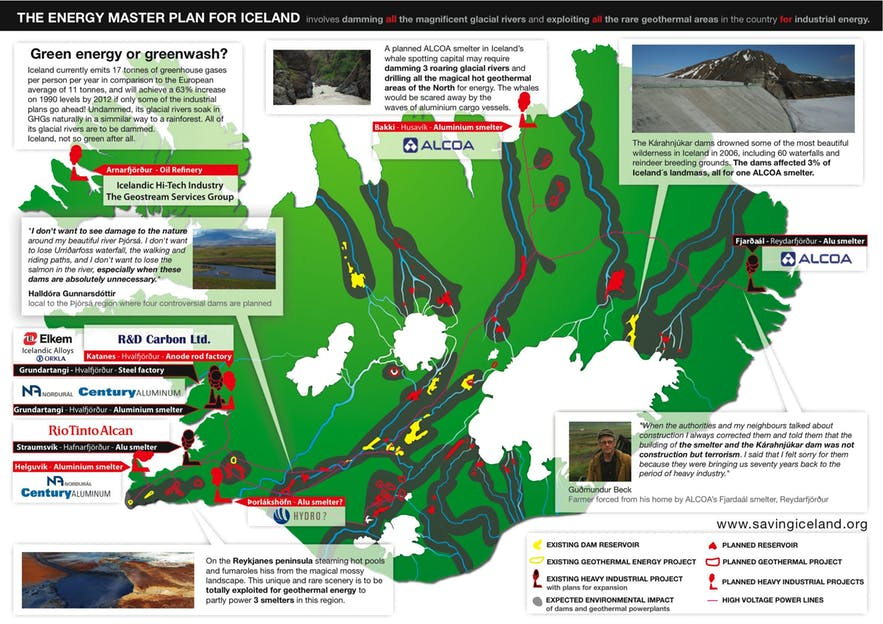

The Energy Master Plan for Iceland. Credit: Saving Iceland

Aluminium smelting relies on a steady electric current (supplied sustainably through geothermal energy) to produce its product; the process means that Hydrogen Fluoride and Carbon Dioxide are released as fumes into the environment, the former of which can become toxic if left unchecked. At last count, levels of sulphur in the soil were found to be just below the acceptable amount. In previous years, the amount of sulphur has far exceeded it.

Those who back the aluminium smelters encourage those protesting it to try and hold onto a global perspective on pollution, claiming that the Icelandic government would be foolish not to capitalise on the wealth of renewable energy that allows the smelters to operate. However, since 1990 to 2007, carbon emissions increased by 26%, almost solely due to the construction and operation of said aluminium smelters.

The Nature of Modern Iceland

When discussing issues concerning the natural world, we as environmentally acute citizens must be cautiously aware of becoming bogged down in abstractions and concepts. The very idea that nature itself can be conceptualised, boxed ‘into an argument’ and politicised to ludicrous extremes is a clear example of confused thinking.

Nature, after all, is interconnected, does not lend itself to language, and radiates a natural order far more complex and staggering than we as the human species can fully comprehend. Our lack of full understanding, however, should not deter from the notion that we are inseparable from it, that our health and wellbeing as individuals is reliant on the protection and prosperity of our habitat.

This sensation of interconnectedness is a matter of course for those willing to appreciate the natural world for its own sake. Sightseeing, hiking, diving, exploration, climbing, caving—in a sense, these are all acts of spiritual liberation, opening new pathways and creating space for gratitude and sensibility.

Nature reserves and national parks across Iceland, by their own right, are standing tributes to this reality, but it is the ‘invisible’ threats of climate change and a warming atmosphere, and the very ‘visible’ threat of wildland violation, that put this organic interrelation into peril.

National Parks & Nature Reserves

Despite Iceland boasting three beautiful National Parks, the government still fails to have a unilateral National Park Service, a central body that can cement and enforce regulations across the board. This, unfortunately, means that this enforcement is left to the individual parks, and more worryingly, to the profit-driven tourist operators shuttling visitors back and forth on a daily basis. Already, one can see an immediate conflict of interests.

Having spent a year myself working for one of these operators, as a tour guide at Silfra Fissure in Thingvellir National Park, I can speak wholeheartedly when I state I have seen firsthand the mistreatment of the environment by visiting tourists.

One major problem, a problem that occurred every single day I worked there, was tourists scrambling and climbing over the precious moss that covers the National Park. Striving to snap a quick photograph, tourists leave their footprints embedded into the moss, a particular breed that struggles with exterior damage and requires a long, long time to repair itself.

I have heard, albeit through the grapevine, that there is a mountain, somewhere in South Iceland, with the name ‘Ben’ having been trodden out by some individual (presumably named Ben.) Regardless, the mountain’s moss has failed to regrow and the name ‘Ben’ still terrorises the untouched aesthetic of the landscape.

Perhaps more recently, pop-star and excitable child, Justin Bieber, was filmed (for his music video, no less) walking across and disrupting the moss, thus setting a terrible example for millions of his fans. If anyone is caught doing this during their stay in Iceland, they will be quickly and justly fined for their efforts.

See also: 5 Reasons Not to Behave like Justin Bieber in Iceland

The conservation group Landvernd is one of many environmental associations trying to establish a new national park in the central highlands. Though the highlands are still largely untouched, the wilderness expanse has sharply fallen in recent years with the continued development of heavy industry, be it dams or hydroelectric plants. This has had an enormously detrimental effect on the highland’s wildlife, aesthetic beauty and natural balance, and has in recent years strengthened the Icelandic people’s opposition to the energy industry.

Iceland’s population are, for the most part, in agreement. Despite nearly 90% of the highlands already being protected, either as part of a nature reserve or national park, further attention is still needed in order to halt the push for further heavy industry, a movement only desired by 10% of the population.

With that being said, Iceland hold does two overarching institutions who deal with environmental affairs; The Environment Agency of Iceland and the Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources. The Environment Agency of Iceland works under the discretion of the Ministry to promote wildlife and animal conservation, the maintenance of outdoor recreation areas, the sustainable use of resources and the continuing development in the field of environmental management, amongst other projects.

Fossil Fuels

Though it is not widely discussed, Iceland still relies on fossils fuels to keep the economy working. Approximately 30% of Iceland’s energy comes from petroleum, fueling vehicles and the entire Icelandic fishing fleet. Given Iceland’s reliance on the fishing industry, fossil fuels play a larger and more important part in the economy than most people realise. This reliance on oil, both for the domestic and international market, cannot be contested, though it is considerably less than that of other nations.

With an increase in tourism and economic stability, more and more shipping lanes have opened within Icelandic coastal waters. Not only does this include fishing trawlers, but oil tankers and ferry services. Though oil spills are rare, should one occur in Icelandic waters, the economy will suffer an enormous blow, with fish stocks taking a major hit.

This, naturally, will correlate negatively to the economy. Given this possibility, the Icelandic government will need to develop a contingency plan as, currently, the country has no capability to deal with an oil spill, nor any other large-scale marine accident.

Climate Change

Despite an overwhelming consensus amongst climate scientists that global warming is not only real but occurring now and caused overwhelmingly by man-made carbon emissions, global warming is still a hot topic in Iceland, as with much of the rest of the world.

Apparently, the Icelandic government has found the reality of the situation a difficult pill to swallow, with some even claiming that the phenomenon is beneficial for Iceland.

For example, former Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson claimed in 2014,

‘There’s a water shortage, energy is becoming more expensive, the land is in short supply and it is predicted that the cost of food will rise in the foreseeable future because of increased demand. So there are great opportunities for Iceland [with global warming] and we are mapping it out.’

Jökulsárlón glacier lagoon has often been cited as ‘ground zero’ for climate change in Iceland, having only begun to form in 1948 after the Breiðamerkurjökull outlet glacier began to quickly recede.

Given that glaciers cover roughly 11% of Iceland’s land mass, and are one of the natural attractions that feed the country’s tourism industry, the disappearance of the ice caps will undoubtedly have an irreversible effect on Iceland’s economy, natural character and geography.

Measures are be taken in an attempt to slow the rate of climate change. The Icelandic government has proposed to increase carbon sequestration from the atmosphere through reforestation, revegetation and the continued preservation of the wetlands. They have also committed to foster further research in fields relating to climate change and climate-friendly technology.

Unfortunately, climate change will not just affect Iceland’s glaciers. Rising temperatures have meant that trees grow around 50% faster than in the last century. Not only that, but tree species that once could not survive Iceland’s climate now flourish, seriously infringing on the natural biodiversity of the island.

An excellent example of how uncontrollable foreign species can be is easily demonstrated by the purple, summer-blossoming lupin flower, a breed that has spread across Iceland at an unprecedented rate.

The flower was originally introduced to Iceland in order to combat soil erosion and soil loss, however, it has since proven to be a threat to native species, particularly the famous Icelandic moss. Today, efforts are being made to reduce the flower’s influence over the ecosystem.

Questions for the Future

Iceland’s era of tourism isn’t going anywhere soon. That’s not to say, however, that the Icelandic people’s patience for tourists and their misbehaviour will last forever. In fact, one could predict the opposite, given the obvious fact that more tourists mean more waste, a higher level of environmental disrespect and further disruption to daily life.

It is education, therefore, and the sharing of conservationist ideas between cultures wherein the protection of Iceland’s environment truly lies. Before arrival even, visitors should be made aware that Iceland’s nature is spiritual. I mean that in the most grandiose of senses, in the same manner, that visitors would not disrespect and destroy holy sites around the world.

First published in Guide to Iceland.