Icelandic Economy Suffers as Century Shareholders Make Record Profit

By Jaap Krater

As inflation rates in Iceland soared to 8.7% and the Icelandic krona lost a third of it’s value, US-based Century Aluminum started construction of a much disputed aluminium smelter at Helguvik, southwest of the capital Reykjavik. The Icelandic economy is suffering from overheating as billions are spent on construction of new power plants and heavy industry projects. The central bank raised the overnight interest rate to a whopping 15% to control further price increases as Icelanders see their money’s value disappearing like snow. It would seem that the last thing the tiny Icelandic economy needs is further capital injections.

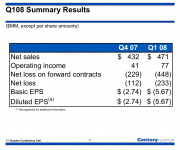

But Icelandic investors are making record profits from the new projects. The value of shares sold to them by Century less than a year ago to finance the Helguvik smelter has increased by 33%, though the company has not made a profit in years.

Environmentalists contend the legality of the project. No environmental impact assessment has been made for the smelter port, power lines or geothermal drilling that threatens large tracts of wilderness. The company has also not secured greenhouse gas emissions quota.

“In essence, Century is running very tough brinkmanship and may end up dictating Iceland’s climate policy as if Iceland were a banana-democracy,” says Arni Finsson from the Iceland Nature Conservation Association.

The issue has become an embarrassing affair for the Icelandic government. Thorunn Sveinbjarnardottir, Minister for the Environment, says she opposes the new Century smelter and other projects. At the same time, Prime Minister Geir Harde is doing his best to negotiate new emission rights for them with the UN. Minister of Industry Ossur Skarphedinsson then commented that the Icelandic government has no control over the development or expansion of aluminum smelters in Iceland anyway.

This is the second time when the government has allowed for a smelter to be built without proper permits. The previous case, ALCOA Fjardaal, has raised Iceland’s per capita emissions from 12 to 18 tons. The European average is 11.

The government still says it aims for a reduction by 50-75 percent from those of 1990, by 2050. “No final decisions have been made on how to accomplish this,” says Anna Kristin Olafsdottir, political adviser to the environment minister, “but a scientific committee is working very hard on a plan.”

International activists from Saving Iceland have decided not to wait while the largest wilderness of Europe is being ruined, and have announced a direct action camp starting July 12th.