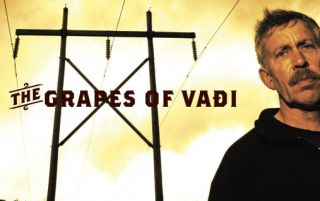

Grapevine Issue 6, August 2004 with update Jan. 2006

In the 1930s, dust storms swept the southern plains of the United States. The “Black Blizzards,” as they were called, had come about because of overfarming, which had caused the topsoil to wear thin and become dust. Crops failed, and as the banks that held the mortgages realised they would not be getting returns on their interest, farmers were run off of their land. Their plight is immortalised in the songs of Woody Guthrie and John Steinbeck’s book “The Grapes of Wrath”, which went on to become a Hollywood film starring Henry Fonda as Steinbeck´s protagonist Tom Joad.

Tom Joad´s shadow has been cast long and wide. How many of the ca. 14 million people so far who´ve read the book have thought to themselves that if they were there, they would have done something, rather than stand idly by as people were evicted from their homes?

This summer has been a warm one on the east coast of Iceland. But the sun has often been obscured by the dust clouds coming down from the construction of the power plant being built at Kárahnjúkar. To make matters worse, the company building the dam, Landsvirkjun, want to build a power line through neighbouring farmer´s lands and are not taking no for an answer. Might they end up as latter day Tom Joad´s? And does anyone give a damn?

A lone farmer speaks up

Guðmundur Ármannsson has lived all his life on his plot of land at Vaði near Egilsstaðir. He´s never been abroad or even to Reykjavík. The farthest he´s ever travelled is to Akureyri, the capital of northern Iceland. He inherited the land from his father, the same family having lived on the land since 1830. Guðmundur took over as farmer 25 years ago and lives there with his wife Gréta Ósk Sigurðardóttir. He´ll be reaching 60, “that awful number,” as he calls it, next year. But now, his peaceful existence has been disturbed. And he´s not happy about it.

“I am unhappy about the powersale agreement. They get the power at a very low price, pay very little taxes and no pollution tax. The land being sacrificed is not being valued at all. They´re also bringing in low cost labour, which will probably bring down wages here in the long run, although, of course, we´re using low cost labour when we buy things manufactured at low pay abroad. And that´s just the economic side of things.”

The Jökulsá River has a very strong current and carries a lot of mud with it that now winds up in the sea. It´s being diverted into the Lagarfljót River, a popular outdoor area here. The colour of Lagarfljót is already changing. The water then winds up in the dam reservoir, along with all the mud it brings. In the summer, when the water level drops, this will lead to the mud being blown as dust all over the countryside. And what happens when eventually the reservoir gets filled up with mud? That will be a problem for future generations. It seems that no one has thought this through. The only explanation they give is that it´s a challenge to engineering.

“This is not negotiation…”

Unlike many, farmer Guðmundur can´t just close his eyes and ignore the construction.

“They´re building a power line through here. The line won´t cross through my land, but they need to build a road to reach it that will. I´m not the one that will be hardest hit by this. Farmer Sigurður Arnarsson over at Eyrarteigar will have the line built right next to his house, and he and I and other people agree that it doesn´t seem like anyone can live in that house anymore after the line is built. He´s being pushed off the land, and for this he is offered 1.200.000 million krónur (roughly 15,000 Euro).”

So what did the company, Landsvirkjun, say to the farmers?

“There was no negotiation. They offer a fixed amount of money, and if you don´t take it they expropriate it. They´ve been getting away with this method. This is not negotiation, this is an ultimatum.”

“Everyone´s drunk on aluminium plants”

And your response?

“I´m not open for negotiation. They came here last November and I said no to them. Then I didn´t hear from them for six months and I thought I was rid of them. Then, about two months ago, they come back. I´ve retained a lawyer, and this is going before the courts. There are at least six other farmers who haven´t signed the contract Landsvirkjun put in front of them either.”

So how do you see the future for this?

I have a bad feeling that in the future people on the East Coast will be blamed for this. Of course it´s the government that made the decision. But people here are ignoring the consequences. It sometimes seems as if everyone´s drunk on aluminium plants. I have a feeling the hangover will be terrible.”

So why has it come to this?

“I think that Icelanders have lost something they used to have, which is love of their country. It´s been sacrificed on behalf of greed. I´m afraid that we won´t be cured of that disease until we have a disaster on our hands. And the longer it takes, the worse it´s going to be.”

Update January 2006.

In August 2004, the Reykjavík Grapevine brought you the story of farmer Guðmundur Ármannsson at Vað near Egilsstaðir. At the time, Guðmundur was in a dispute with the National Power Company, Landsvirkjun, over the rights to build an access road through his land, for power lines to deliver electricity from Kárahnjúkar to the aluminium smelter in Reyðarfjörður. Guðmundur was having none of it. Later Guðmundur allowed a group of demonstrators to camp out on his land and conduct their operations from there, after the group had been chased off of their original camping site near Kárahnjúkar. The Reykjavík Grapevine spoke to Guðmundur to get an update on his dealings with Landsvirkjun.

So, what has happened since we last spoke to you?

– Not much. Landsvirkjun decided to go a different route. I refused to give them permission to go through my land and that was that.

What about the surrounding farmers?

– Well, the farmer at Eyrarteigur decided to call it quits. The power line was being built 100 meters from his house and he decided that living so close to a power line that big was not a viable option.

At first the farmer at Eyrarteigur was only being offered 1,200,000 ISK as settlement for the use of his land, was that the final outcome?

– I believe he managed to get about the worth of the house from Landsvirkjun. He moved to Akureyri.

Has the attitude among the locals changed in any way?

– People are worried about the economic outcome in the long run. There is a lot of money in traffic, but most of it does not belong to us. We are just borrowing it. People worry about economic downturn that is going to follow once the construction is over.

How was your experience having a demonstration camp living on your land?

– It was very good. Everyone was very polite and considerate. I would never have trusted a group of Icelanders of this size to camp out on my land.

Do you believe that a concert like this will raise awareness of the issue?

– It does a great deal, without question. I think it is a very respectable enterprise. I think that the dispute over Kárahnjúkar is going to help others in their fight to preserve areas that Landsvirkjun wants to go after. I believe that eventually Kárahnjúkar is going to be a monument to stupidity and short-sightedness.