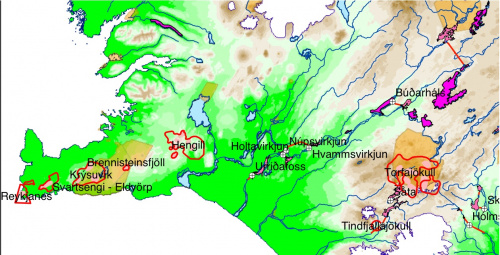

Þjórsá, Tungnaá and Köldukvísl rivers

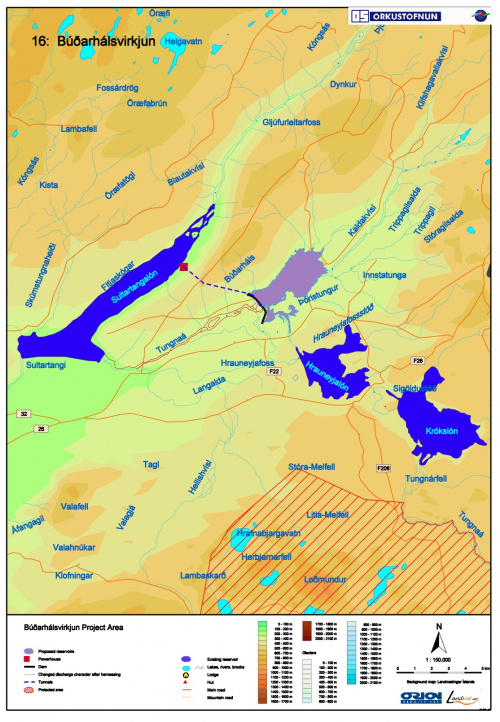

Updated August 2008 – Þjórsá is the longest river in Iceland and was in the past the most significant river for hydropower production, before construction of the Karahnjukar dams. The rivers are imminently under threat. Landsvirkjun wishes to build three power plants, Hvammur (82 MW), Holt (53 MW) and Urriðafoss (130 MW) as soon as possible, and is as of now (August 2008) starting with work on a dam higher up in Tungnaá and Köldukvísi, named Búðarhálsvirkjun (80 MW).

The energy from Búðarhálsvirkjun would almost completely (75 MW) go to a production expansion of 40.000 tons per year of Rio Tinto Alcan’s smelter at Straumsvik, just south of Reykjavik. The remainder is for a data centre in Keflavík by Verne Holding.

Landsvirkjun will not say exactly what the energy from the Þjórsá dams is meant for and just generally states it wants to attract more data centres and silicon refineries to be located in Thorlakshöfn. However, it is impossible that Landsvirkjun will be able to find enough companies to establish themselves to fully utilise the the total of 265 MW that is remaining. The labour market is very tight in Iceland; even if Landsvirkjun would offer the cheapest energy in the world, the labour market would limit the amount of high-tech industries that can be established and it would be likely that the remaining energy would go to further aluminium expansion.

These dams would receive increased capacity if the planned projects at Langisjór and Thjorsarver are also executed, producing enough for another medium sized smelter.

Another option is that the energy will be used for the city of Reykjavík, freeing energy from the existing Blanda dam in the north, which could go to increasing the projected size of Alcoa’s planned Bakki smelter in Husavík.

The Þjórsá dams are heavily opposed by the local population and a lawsuit from one of the local farmers is currently stopping Landsvirkjun from pursuing the dams. The farmers are also refusing to sell their land, and Landsvirkjun has mentioned the possibility of forced expropriation of local landowners if they do not cooperate.

The Þjórsá and Tungnaá dams are again an illustration of the infamous catch-22 Landsvirkjun-logics. The lower Þjórsá dams are in areas that are inhabited and used by farmers. Therefore, according to Landsvirkjun, they are not wilderness so the environmental impact is not as big, so it is no problem building dams there. But dams like Búðarhálsvirkjun, are in more or less uninhabited area, so it is no problem to build them as they do not affect anyone.

The work on Búðarhálsvirkjun stopped in 2002 when the dam was deemed economically infeasible. The landscape has already been severely impacted by explosives and bulldozing.

Below: Háifoss in Fossá, a tributary of Þjórsá.

Below: Uridafoss in Þjórsá

Below: Dynkur in Þjórsá. The waterfalls have been made innaccessible in preparation for their destruction (and to erase them from peoples memories). A roadsign at the entrance track to the falls (incorrectly) says the road is blocked.

Click map to enlarge