After thirteen years of environmental, economic and technical evaluations, followed by a proposition for a parliamentary solution and a three month long public comments process, wherein 225 reviews where handed in — we are now witnessing the final steps in the making of Iceland’s Master Plan for Hydro and Geothermal Energy Resources. The plan, which in diplomatic language is supposed to “lay the foundation for a long-term agreement upon the exploitation and protection of Iceland’s natural resources,” has now been presented as a bill by the Ministers of Environment and of Industry, respectively, and is currently awaiting discussion and further bureaucratic processes in parliament.

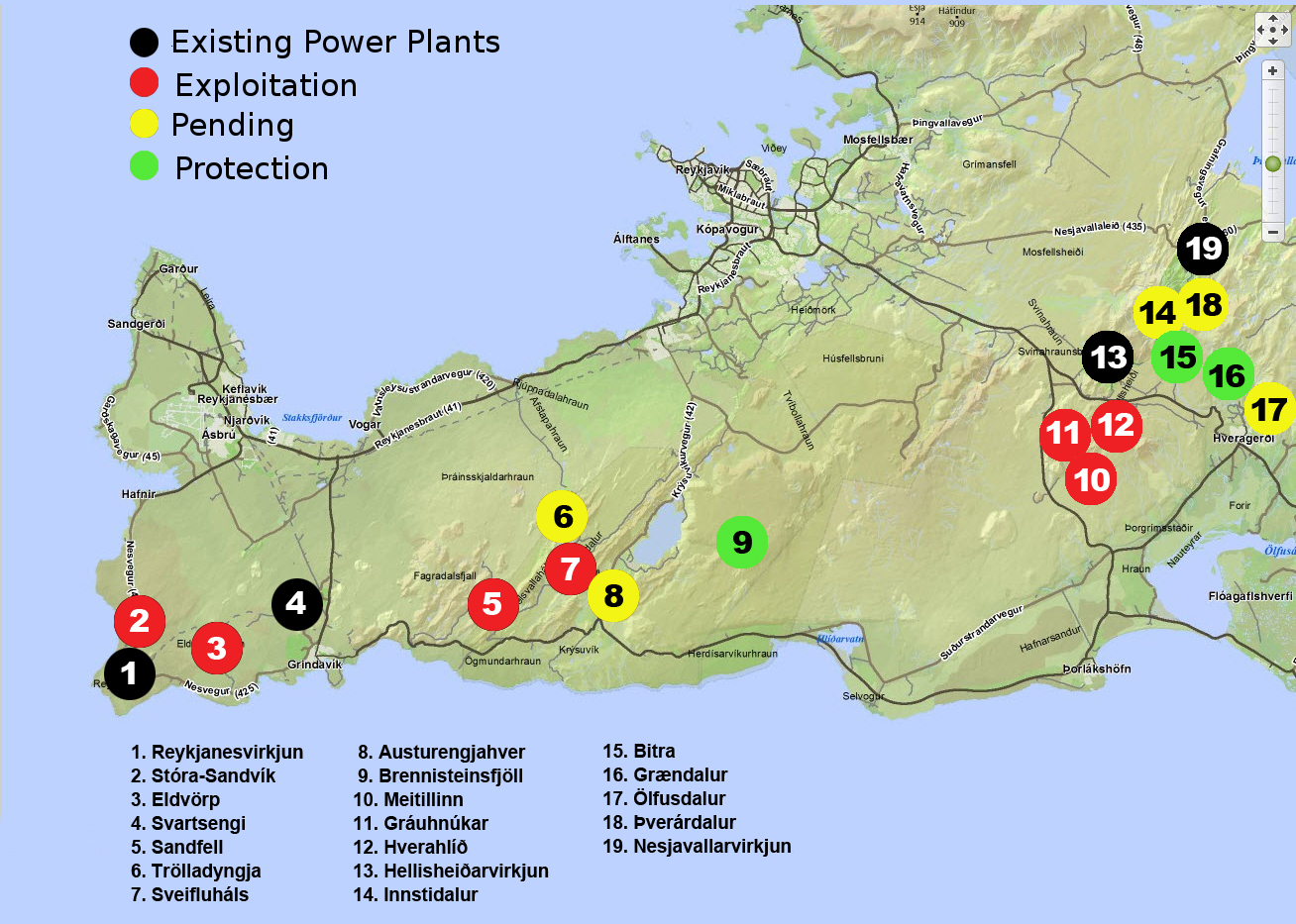

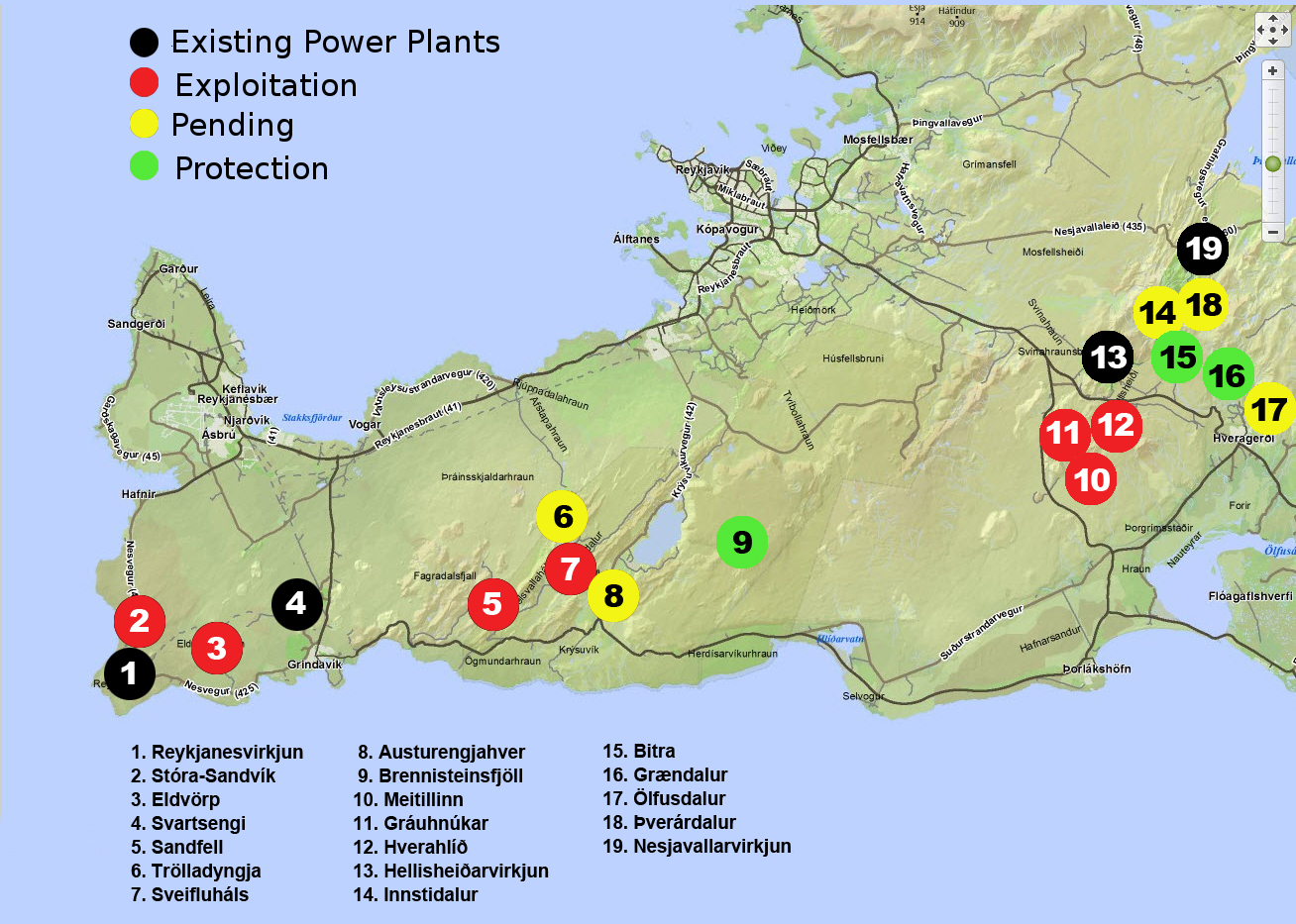

Treated as the Master Plan’s trash can, the unique geothermal areas on the Reykjanes peninsula get a particularly harsh deal. Out of the peninsula’s nineteen energy potential areas, only three are listed for protection while seven are set for exploitation in addition to the four that have already been harnessed. Five additional areas are kept pending, more likely than not to be set for exploitation later. Existing plans for energy production outline how the peninsula is set to be turned into a single and continuous industrial zone, and the power companies seem to be simply waiting for a further green light to exploit the area. All this in order to further feed the aluminium industry.

In this overview we take a look at nine of these nineteen areas — those from the west of Gráuhnúkar — of which only one is to be protected according to the Master Plan. We look at the plans on the drawing board, their current status, the key companies involved, the already existing power plants, the threatened areas, and at last but not least: possible targets for direct action. On the map below, these areas are marked from number one to nine. Obviously the map only shows the areas at stake and the reader has to use her or his imagination to fill in power lines and the rest of the necessary infrastructure. Most of the following photos are taken by Ellert Grétarsson — click here and here for more of his photos.

Unmasking the Geothermal Myth

In a world increasingly concerned about carbon emissions,” Jaap Krater and Miriam Rose state, “the clean image of hydroelectric and geothermal energy is appealing.” This has certainly been the case in Iceland, where the highly polluting aluminium industry has attempted to re-model their dirty image by powering their production with so-called ‘green energy’. However, this greenwashing has not entirely worked as the eastern highland’s Kárahnjúkar dams — fully built in 2007 to power an Alcoa aluminium smelter in Reyðarfjörður — have proven to be as ecologically and economically disastrous as environmentalists warned. As a result the aluminium companies have now mostly moved from hydro and instead are increasingly focussing on geothermal energy.

One of the companies is Norðurál, subsidiary of Century Aluminum, who claim that their planned 360 thousand ton aluminium smelter in Helguvík will be one the world’s most environmentally friendly smelters. Why so? Because according to the company, the 625 MW of electricity required to run a smelter of this size is supposed to come only from the peninsula’s geothermal energy sources. However, environmentalists and scientists consider the estimation of geothermal energy believed to be extractable from the peninsula to be highly over-estimated, and claim that

additional hydro power plants would be needed to power the smelter. This would most likely come from the much-debated and

now temporarily halted dams in the river of lower Þjórsá.

Last year, unable to access the necessary geothermal energy in north Iceland, aluminium company Alcoa was forced to withdraw their six years long plan to build a geothermal powered smelter at Bakki, Húsavík. We predict that if Century cannot force through the damming of lower Þjórsá a similar situation awaits Helguvík. But that has not stopped the project’s interested parties, who still state confidently that the smelter will be built, and powered with geothermal energy.

Regardless of the need for additional hydro power, the exploitation of the Reykjanes peninsula’s geothermal areas spells the end of this magnificent nature of the peninsula as we know it. Test drilling and boreholes, endless roads and power lines, power plants and other infrastructure; all this would turn the Reykjanes peninsula — this unique land of natural volcanic wonders, which many scientists and environmentalists believe to be one of the world’s best options for creating a giant volcano park with educational and tourism-related opportunities — into a large industrial zone.

But these are only the very visible impacts of the planned large-scale exploitation. Other environmental catastrophes are in fact inevitable with large scale geothermal industry, becoming increasingly visible to the public as the green reputation of geothermal energy slowly decreases.

Two of Saving Iceland’s spokespersons — ecological economist Jaap Krater and geologist Miriam Rose — have thoroughly analysed the development of Iceland’s geothermal potential in a chapter, written on behalf of Saving Iceland, and recently published in a book on the current energy crisis. While we strongly recommend the piece for further reading about the geothermal myths, a few of their points will be addressed here, with relevance to recent events in Iceland.

Firstly, geothermal gases are rich in a variety of harmful elements and chemical compounds such as sulphur dioxide, whose impacts are systematically underestimated according the Public Health Authority of Reykjavík. Since production began at the Hellisheiði geothermal power plant — often claimed to be the biggest of its kind in the world — in 2006, a 140 percent increase of sulphur pollution has been measured in the capital area of Reykjavík, only 30 kilometres away. Recent studies, conducted by the University of Iceland, suggest a direct link between increased sulphur pollution on the one hand, and increased use of medicine for asthma and heart disease ‘angina pectoris’ on the other hand. However, engineering firms such as Mannvit, authors of many of the Environmental Impacts Assessments for geothermal power-plants, have so far ignored these studies and instead based their assessments on so-called prediction models. (Read more about the sulphur pollution

here and

here.)

Secondly, at the end of last year it was revealed that for two years energy company Reykjavík Energy — who own and operate the Hellisheiði plant — had on occasions been pumping waste water containing hydrogen sulphide into drinking water aquifers. Sulphides are far from being the plants’ only damaging effluents entering our water system; Krater and Rose mention that “geothermal fluids contain high concentrations of heavy metals and other toxic elements, including radon, arsenic, mercury, ammonia, and boron.”

Thirdly, it is suggested that depletion of one geothermal reservoir can result in the drying up of surrounding hot spring areas. While large-scale exploitation in Iceland is probably too young to witness these effects, environmentalists and geologists have warned that exactly this will happen in the Reykjanes peninsula if the existing plans go ahead.

The Key Companies Involved

HS Orka

HS Orka is an energy company that owns and operates two geothermal power plants on the peninsula — Reykjanesvirkjun and Svartsengi — the majority of who’s energy goes to Norðurál’s aluminium smelter in Grundartangi, Hvalfjörður. HS Orka’s majority shareholder is Magma Energy Sweden A.B., a puppet company of the Canadian firm Magma Energy, which was established to get around laws that prevent non-Europeans from buying Icelandic companies. After Magma’s 66,6% share, the remaining 33,4% is owned by Icelandic pension funds.

Before privatisation HS Orka (then called Hitaveita Suðurnesja) was owned fifty-fifty by the Icelandic state and several municipalities on the country’s south-west coast, but in 2007 the state’s share was sold to a private company named Geysir Green Energy (GGE). Following laws passed in 2008, regarding the separation of private energy production from competitive operations, the company became two different firms — HS Veitur and HS Orka — of which the latter takes care of energy production and sales. Bit by bit, GGE bought up two thirds of HS Orka’s shares. In 2009, GGE sold extra 10% to Magma Energy, which at the same time bought 32% from another energy company, Reykjavík Energy, and the nearby municipality of Hafnarfjörður. At this point GGE owned 55% of HS Orka and Magma owned 43%.

Harsh criticism arose over these deals which were effectively privatisation of Iceland’s natural resources, including a campaign led by pop-singer Björk and Eva Joly, the recent French Green Party presidential candidate, who at that point served as the Icelandic center-left government’s special financial advisor, following the general elections in 2009. Asked if the company was considering majority stake in HS Orka, Magma’s CEO Ross Beaty replied with a straight “no”. He then emphasised that the company would not buy more than 50% of the shares, as had officially been accepted by Iceland’s government, calling this “a rather awkward business position but certainly something that we feel can be workable.”

However, in 2010 Geysir Green Energy sold all their shares to Magma, which now owned 98.5% of HS Orka. A year later Magma sold 25% to Jarðvarmi slhf, a company owned by fourteen Icelandic pension funds, which a little later bought additional 8.4%. At last, Magma bought the 1.5% still owned by four different municipalities. Thus Magma holds 66.6% of the shares today, while Jarðvarmi owns 33.4%. The land use rights held by Magma allow for 65 years exploitation with an option to extend this for another 65 years.

Alterra Power

Just as the name could not have been coloured with more controversy and scepticism, Magma Energy merged with Plutonic Power and became Alterra Power, a company traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The new company’s Executive Chairman Ross Beaty, said that the merger would “strengthen both companies and […] create a larger, more diversified renewable energy company.” He further stated: “Geothermal will remain a core focus of the new company, but hydro, wind and solar assets will be solid business platforms for future growth. In the renewable energy business, bigger is better and this combination will achieve that while enhancing returns to each company’s shareholders.”

Alterra Power already operates geothermal, hydro and wind power plants in Nevada and British Columbia, which together with the Iceland plants have the energy capacity of 570 MW. In the company’s own words, they have a “strong financial capacity to support [their] aggressive growth plans,” which include geothermal plants in Chile and Peru. Such Latin-American adventures are certainly not new to the company’s key people, as Ross Beaty founded and currently serves as Chairman of one of the world’s largest silver producers, Pan American Silver, with some of its mines in Peru.

For the last three decades in fact Beaty has founded and divested a series of mineral resource companies, but has now shifted his focus to the ever-enlarging economy of ‘green energy’. As he explained himself: “This time around I wanted to build something green, so I looked at geothermal and it was just perfect, it just fit”. When confronted with the possibility that he and his company were taking advantage of Iceland’s economic collapse — a theory supported by the words of John Perkins, the author of ‘Confessions of an Economic Hitman’ — he called such ideas “ignorance and complete nonsense.” Only a few months later, he nevertheless said to Hera Research Monthly, an online investment newsletter, that “going into Iceland was strictly something that could only have happened because Iceland had a calamitous financial meltdown in 2008.”

Norðurál

Norðurál is a subsidiary of North-American aluminium producer Century Aluminum, whose largest shareholder is commodity broker Glencore International, a company that controls almost 40% of the global aluminium market. Glencore is mostly known for its many tentacles of corruption and worldwide human rights and environmental violations — most recently manifested in the exposure of child-labour in the company’s copper mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as the dumping of acid into a river at another site in the same country.

Norðurál currently operates an aluminium smelter in Hvalfjörður, which was fully built in 1998 despite harsh opposition by the fjord’s inhabitants. The smelter has been enlarged in a few phases, seeing the production capacity going from the original 60 thousand tons per year, to the current 278 thousand tons. Since 2004, the company has invested 20 billion ISK into building another Iceland smelter, in Helguvík on the north-west tip of the Reykjanes peninsula. According to the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), the smelter is supposed to be powered solely by the peninsula’s geothermal energy — a claim that environmentalists and geologists have seriously questioned.

In April 2007, HS Orka signed a contract with Norðurál, promising the latter company 150 MW of energy for the Helguvík smelter’s first phase, supposed to be extracted by the planned expansion of the Reykjanesvirkjun geothermal power plant. Three years later, when no energy had been made available, the aluminium company filed charges against HS Orka for non-compliance. The conflict ended up in an arbitration court in Sweden, the registered home country of HS Orka’s owner, Magma Energy Sweden. Officially the conflict was presented to the public as a matter of energy prices but in late 2011 the court ruled that HS Orka is obliged to provide Norðurál the originally agreed-upon energy, suggesting that the conflict had to do with more than prices.

Already Existing Power Plants

Reykjanes

Reykjanesvirkjun is a 100 MW plant, owned by Alterra Power, whose energy partly powers Norðurál’s smelter in Hvalfjörður. It is located on 410 hectares of land located at the south-west tip of the peninsula. The company has plans for at least an 80 MW expansion of the plant, which is supposed to take place in two 50 and 30 MW phases, that according to HS Orka should both be completed in 2013.

However, following conditions set by Iceland’s National Energy Authority (NEA) last year, the expansion plans have become a bit more complicated. In order for it to happen, at least 30 out of the 50 MW included in the first phase have to come from another area than currently planned. Further extraction in the already exploited area would simply be unsustainable and decrease the area’s capacity. Geologist Sigmundur Einarsson actually believes that the field is already over-exploited. His claim is based on studies from 2009, by the very same NEA, which state that the area’s long-term sustainable production capacity is hardly more than 25 MW.

Svartsengi

The Svartsengi plant is operated by HS Orka and is located on 150 hectares of land owned partly by the municipality of Grindavík and partly privately. Next to it stands the Blue Lagoon, a tourist attraction created by the brine pollution from the power plant. The plant is a combined electricity and heat plant with a current electric power capacity of 75 MW, of which most goes to Norðurál’s smelter in Hvalfjörður.

The Threatened Areas

Eldvörp

The Master Plan gives a green light for the exploitation of Eldvörp, a 15 km long row of craters, located four km south-west of Svartsengi. Svartsengi and Eldvörp are thought to share a geothermal aquifer, which many claim to be fully exploited already. Thus even the smallest energy production would be unsustainable. Alterra Power still has plans to build a 50 MW power plant in Eldvörp, for which both research and utilization leaves have been granted. The planned plant is on land owned by the municipality of Grindavík, which apparently is about to finish the required land use plan enabling the project to take place.

The geothermal field is situated at the heart of the row of craters. There are only a few signs of geothermal activity on the actual surface, only fumaroles the lavafield and steam wisps when the weather is mild. One single borehole has already been constructed close to one of the craters at the centre of Eldvörp. It’s environmental impact is very limited compared with the impacts of the planned over-all drilling and the appendant pipelines, power lines, roads, powerhouse separator building. Such construction will have enormously destructive impacts on both natural and cultural relics in the area, including the row of craters and the Sundvörðuhraun lavafield.

Stóra-Sandvík

Stóra-Sandvík is a unique geothermal field in a coastal area close to the municipalities of Grindavík and Hafnir, as well as to the Reykjanesvirkjun plant, which in itself should be reason enough to move it from the exploitation category and instead to protection.

Krýsuvík

This geothermal area consists of four subfields — Sandfell, Trölladyngja, Sveifluháls and Austurengjar — which all connect to the same volcanic system, usually just named Krýsuvík. The geothermal activity is located at the margins of the system’s fissure swarms, while the Núpshliðarháls tuff ridge lies closer to its centre, with thousands of years old lava flats and eruptive fissures on both sides. Where the tuff has tightened due to geothermal transformations, small streams flow on to the lavafields and have thus created vegetated areas such as Höskuldsvellir, Selsvellir, Vigdísarvellir and Tjarnarvellir. As from the west of Hellisheiði, hardly any water runs on the surface of the whole Reykjanes mountain range, save the above-mentioned areas of Krýsuvík.

Interestingly, Krýsuvík is directly linked to what many consider to be the origins of environmentalism in Iceland. A geologist and environmentalist named Sigurður Þórarinsson, who had often voiced his concerns regarding Icelanders’ treatment of the country’s natural environment, had become seriously alarmed by what he witnessed by the Grænavatn maar in Krýsvík. It was, Sigurður said, used as a trash can for construction projects in the nearby area. At a meeting at the Icelandic Ecological Society in 1949, Sigurður suggested the creation of a legislation regarding nature conservation. Shortly afterwards, he was asked to take part in designing the legislation, which was passed in 1956 — the first in Iceland’s history. (Read about Sigurður Þórarinsson here.)

Out of the four Krýsuvík areas, the Energy Master Plan allows for the exploitation of Sandfell and Sveifluháls, while Trölladyngja and Austurengjar are supposed to be pending until the results of drilling in the two former areas are known. The National Energy Authority claims that these combined 89 km2 of land should have the production capacity of 445 MW of energy for 50 years, and as such be Iceland’s third most powerful geothermal field after the Hengill and Törfajökull areas. However, independent scientists and environmentalists have seriously questioned these figures, believing the area’s maximum possible production capacity to be 120 MW for 50 years.

Sandfell

Sandfell area is a semi-unspoiled volcanic area of lavafields and tuff mountains, large vegetated flatlands, and beautifully formed craters. It is a uniquely colourful area, which will be permanently altered if HS Orka’s planned 50 MW power plant will be built. The company has already been granted permission for test drilling and one borehole has been test-drilled, but no results have yet been published.

Sveifluháls (Krýsuvík)

Sveifluháls is a 20 km broad and 150 to 200 meter high compounded and mostly non-vegetated tuff ridge. The 2-3 km long geothermal area of fumaroles, mud springs and muddy hot springs — usually referred to as simply ‘the Krýsuvík geothermal area’ — lies a little east of the Krýsuvík fissure swarm. Despite drilling done in the second half of the 20th century, the area is relatively unspoiled and could easily be brought back close to its natural state. Due to the tuff transformation, the area is especially rich in colour and contains unusual geothermal salt deposits and gypsum. The area is unique due to its many maars, for instance Arnarvatn and Grænavatn (pictured above), of which some show signs of Holocene volcanic activity. Sveifluháls is a popular stopover as well as an outside school-room for geology. It also contains historical relics of human residence, as far back as Iceland’s original settlement.

There are plans to operate a 50-100 MW power plant in the area — a construction that would include somewhere between 10 and 20 boreholes, road construction, pipelines and power lines to connect the plant to the national energy grid. HS Orka has a research leave in the area but has not been able to guarantee the utilization rights, which are owned by the municipality of Hafnarfjörður.

Austurengjar

The geothermal area of Austurengjar is about 1.5 km east of lake Grænavatn — a relatively flat and mostly unspoiled area of mud pots, hot springs and dolerite ridges, which slopes north to lake Kleifarvatn. As a result of earthquakes in 1924, the geyser activity increased dramatically and since then, Austurengjahver has been the area’s most powerful spring. This colourful geothermal area is special as it lies completely outside of Krýsuvík’s volcanic system and shows no signs of Holocene volcanic activity. The plans for a 50 MW power plant at Austurengjar, including 10 to 15 boreholes and a whole lot of power lines, would directly impact the whole area and change the face of lake Kleifarvatn, which is today a wild and unspoilt lake, surrounded by mountains.

Trölladyngja

Trölladyngja is one of the three mountains (the other two being Grænadyngja and Fífavallafjall) that together make up the north-east end of a 13 km long tuff ridge called Núpshlíðarháls, which lies within Krýsuvík’s volcanic system. The geothermal area is about three km long and seems to be partly connected to extension fractures in the system. South of the mountains, a small stream called Sogalækur has shovelled out a considerable amount of clay and thus formed a colourful canyon called Sogin. The stream deposited the clay into the lava below and formed the vegetated field Höskuldarvellir. HS Orka has for many years had plans to build a power plant in Trölladyngja and three holes have been drilled already, resulting in very limited success but a lot of disruption. The Trölladyngja area is partly included in the Natural Heritage Register.

Protected Area(s)

Brennisteinsfjöll

Only one out of the peninsula’s nine potential energy generating areas will be protected if the Master Plan goes through parliament unaltered. Brennisteinsfjöll are a row of mountains, considered an impenetrable part of the Krýsuvík area, and do in fact constitute the largest untouched wilderness around the capital area of Reykjavík. As highlighted by Krater and Rose: “Wilderness areas are becoming rare globally, with over 83 percent of the earth’s landmass directly affected by humans, and the Icelandic wilderness is one of the largest left in Europe.”

Possible Targets for Protests and Direct Actions

The Ministry of Environment

Skuggasund 1

150 Reykjavík

The Ministry of Industry

Arnarhváll by Lindargata

150 Reykjavík

HS Orka

Brekkustígur 36

260 Reykjanesbæ

Jarðvarmi slhf

Stórhöfða 31

110 Reykjavík

Norðurál Grundartangi ehf (smelter and offices)

Grundartangi

301 Akranes

Norðurál Helguvík ehf (only offices)

Stakksbraut 1

Garður

232 Reykjanesbæ

Helguvík Smelter

See location on map here.

Century Aluminum Company (Corporate Headquarters)

2511 Garden Road

Building A, Suite 200

Monterey,

CA 93940

USA

For a list of more offices and smelter click here.

Alterra Power Corp. (Corporate Offices)

600-888 Dunsmuir Street

Vancouver, BC

Canada V6C 3K4

For a list of more Alterra Power offices click here.

Glencore International

Registered Office

Queensway House

Hilgrove Street

St Helier

Jersey

JE1 1ES

Headquarters

Baarermattstrasse 3

P.O. Box 777

CH 6341 Baar

Switzerland

_______________________________________________________

Main Sources

Áhugahópur um verndun Jökulsánna í Skagafirði, Eldvötn – samtök um náttúruvernd í Skaftárhreppi, Félag um verndun hálendis Austurlands, Framtíðarlandið, Fuglavernd, Landvernd, Náttúruvaktin, Náttúruverndarsamtök Austurlands (NAUST), Náttúruverndarsamtök Íslands, Náttúruverndarsamtök Suðurlands, Náttúruverndarsamtök Suðvesturlands, Samtök um náttúruvernd á Norðurlandi (SUNN), Sól á Suðurlandi. Umsögn um drög að tillögu til þingsályktunar um áætlun um vernd og orkunýtingu landsvæða. 11. nóvember 2011. (Download PDF here.)

Krater and Miriam Rose on behalf of Saving Iceland, “Development of Iceland’s Geothermal Energy Potential for Aluminum Production — A Critical Analysis”. In: Abrahamsky, K. (ed.) Sparking a World-wide Energy Revolution: Social Struggles in the Transition to a Post-Petrol World. 2010, AK Press, Edinburgh. p. 319-333. (Download PDF here.)

Various information from Náttúrukortið (The Nature Map) on the website of environmentalist NGO Framtíðarlandið (The Future Land).

Sigmundur Einarsson, Hinar miklu orkulindir Íslands, Smugan.is, October 2009.

Sigmundur Einarsson, Er HS Orka í krísu í Krýsuvík?, Smugan.is, November 2009.

Sigmundur Einarsson, Ómerkilegur útúrsnúningur iðnaðarráðherra, Smugan.is, November 2011.

Sigmundur Einarsson, Er HS Orka á heljarþröm?, Smugan.is, December 2011.

Catharine Fulton, Blame Canada? Geothermal energy, Swedish shelf companies and the privatisation of Iceland, The Reykjavík Grapevine, October 2009.

Catharine Fulton, Magma Energy Lied to Us, The Reykjavík Grapevine, May 2010.

Volcano Park to Open in Iceland? Iceland Review, July 2007.

Various information from the websites of Alterra Power, HS Orka and Norðurál.